Rate Limiter Architecture

The main architectural question is: where should we place the rate limiter in our application stack?

This largely depends on the configuration of the application stack. Let’s examine this in more detail.

The location where we integrate our rate limiter into our application stack matters significantly. This decision will depend on the rate limiting requirements we gathered in the previous section.

In the case of typical web-based API-serving applications, we have several layers where rate limiters could potentially be placed.

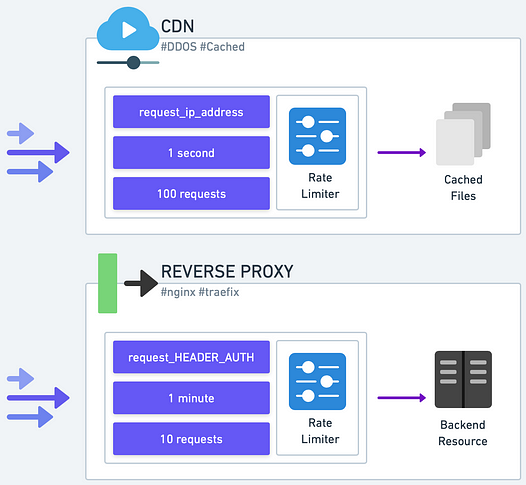

CDN and Reverse Proxy

The outermost layer is the Content Delivery Network (CDN) which also functions as our application’s reverse proxy. Using a CDN to front an API service is becoming an increasingly prevalent design for production environments. For example, Cloudflare, a well-known CDN, offers some rate limiting features based on standard web request headers like IP address or other common HTTP headers.

If a CDN is already a part of the application stack, it’s a good initial defense against basic abuse. More sophisticated rate limiters can be deployed closer to the application backend to address any remaining rate limiting needs.

Some production deployments maintain their own reverse proxy, rather than a CDN. Many of these reverse proxies offer rate limiting plugins. Nginx, for example, can limit connections, request rates, or bandwidth usage based on IP address or other variables such as HTTP headers. Traefik is another example of a reverse proxy, popular within the Kubernetes ecosystem, that comes with rate limiting capabilities.

If a reverse proxy supports the desired rate limiting algorithms, it is a suitable location for a basic rate limiter.

However, be aware that large-scale deployments usually involve a cluster of reverse proxy nodes to handle the large volume of requests. This results in rate limiting states distributed across multiple nodes. It can lead to inaccuracies unless the states are synchronized.

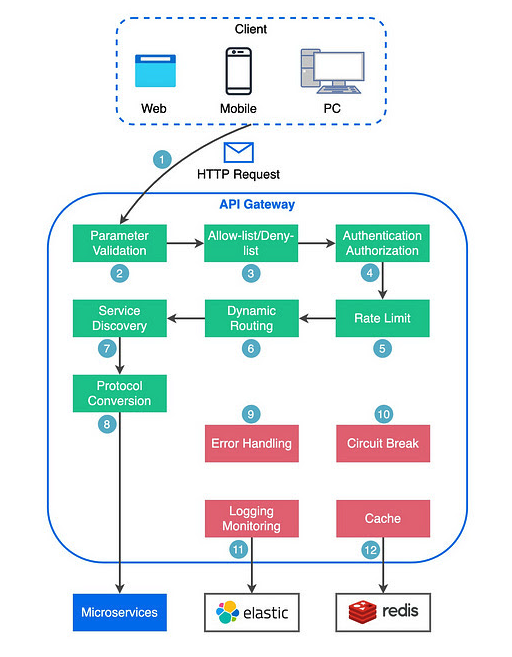

API Gateway

Moving deeper into the application stack, some deployments utilize an API Gateway to manage incoming traffic. This layer can host a basic rate limiter, provided the API Gateway supports it. This allows for control over individual routes and lets us apply different rate limiting rules for different endpoints.

Amazon API Gateway is an example of this. It handles rate limiting at scale. We don’t need to worry about managing rate limiting states across nodes, as would be required with our own cluster of reverse proxy servers. A potential downside is that the rate limiting control might not be as fine-grained as we would like.

Application Framework and Middleware

If our rate limiting needs require more fine-grained identification of the resource to limit, we may need to place the rate limiter closer to the application logic. For example, if user specific attributes like subscription type need limiting, we’ll need to implement the rate limiter at this level.

In some cases, the application framework might provide rate limiting functionality via middleware or a plugin. Like in previous cases, if these functions meet our needs, this would be a suitable place for rate limiting.

This method allows for rate limiting integration within our application code as middleware. It offers customization for different use-cases and enhances visibility, but it also adds complexity to our application code and could affect performance.

Application

Finally, if necessary, we could incorporate rate limiting logic directly in the application code. In some instances, the rate limiting requirements are so specific that this is the only feasible option.

This offers the highest degree of control and visibility but introduces complexity and potential tight coupling between the rate limiting and business logic.

Like before, when operating at scale, all issues related to sharing rate limiting states across application nodes are relevant.

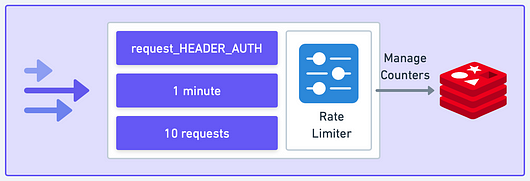

Rate Limiting States

Another significant architectural decision is where to store rate limiting states, such as counters. For a low-scale, simple rate limiter, keeping the states entirely in the rate limiter’s memory might be sufficient.

However, this is likely the exception rather than the rule. In most production environments, regardless of the rate limiter’s location in the application stack, there will likely be multiple rate limiter instances to handle the load, with rate limiting states distributed across nodes.

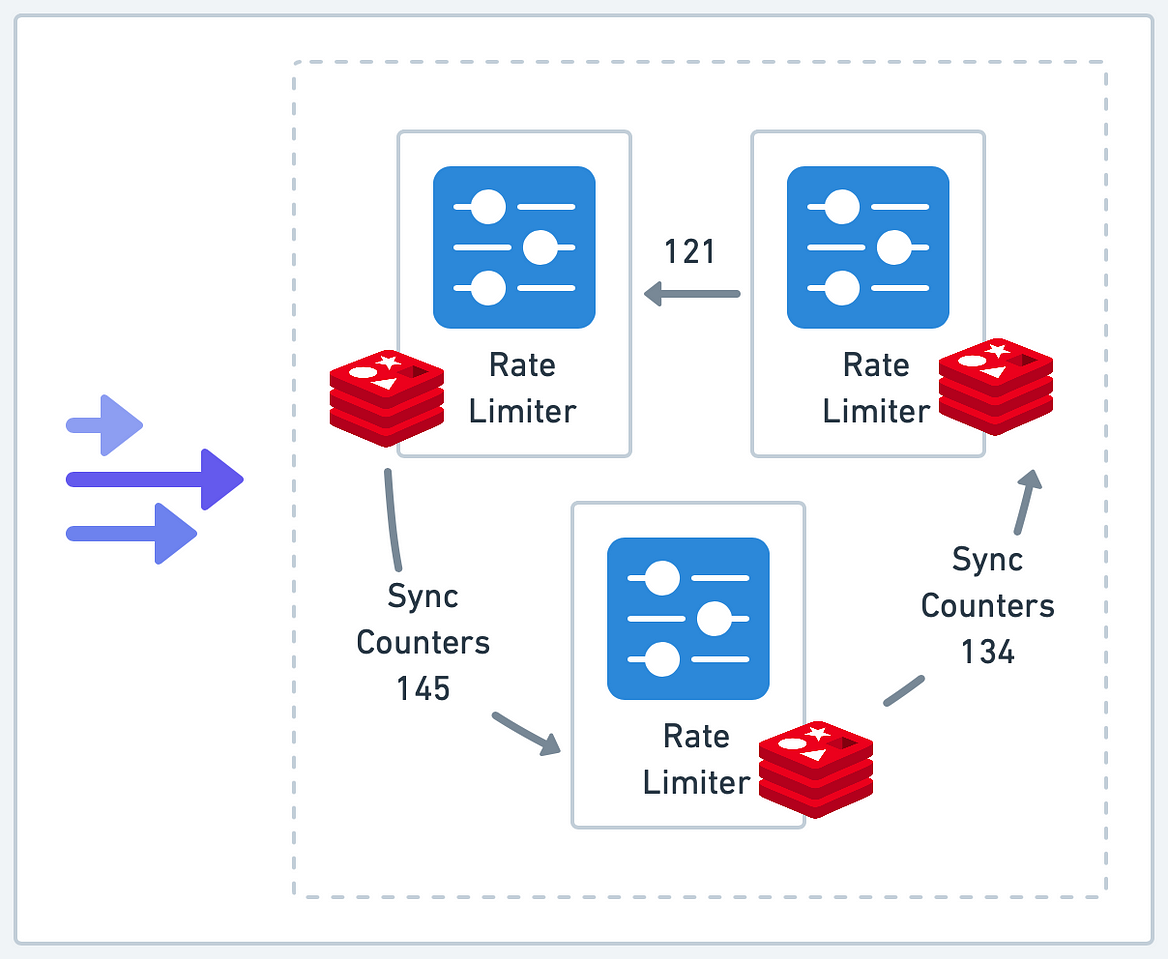

We’ve frequently referred to this as a challenge. Let’s dive into some specifics to illustrate this point.

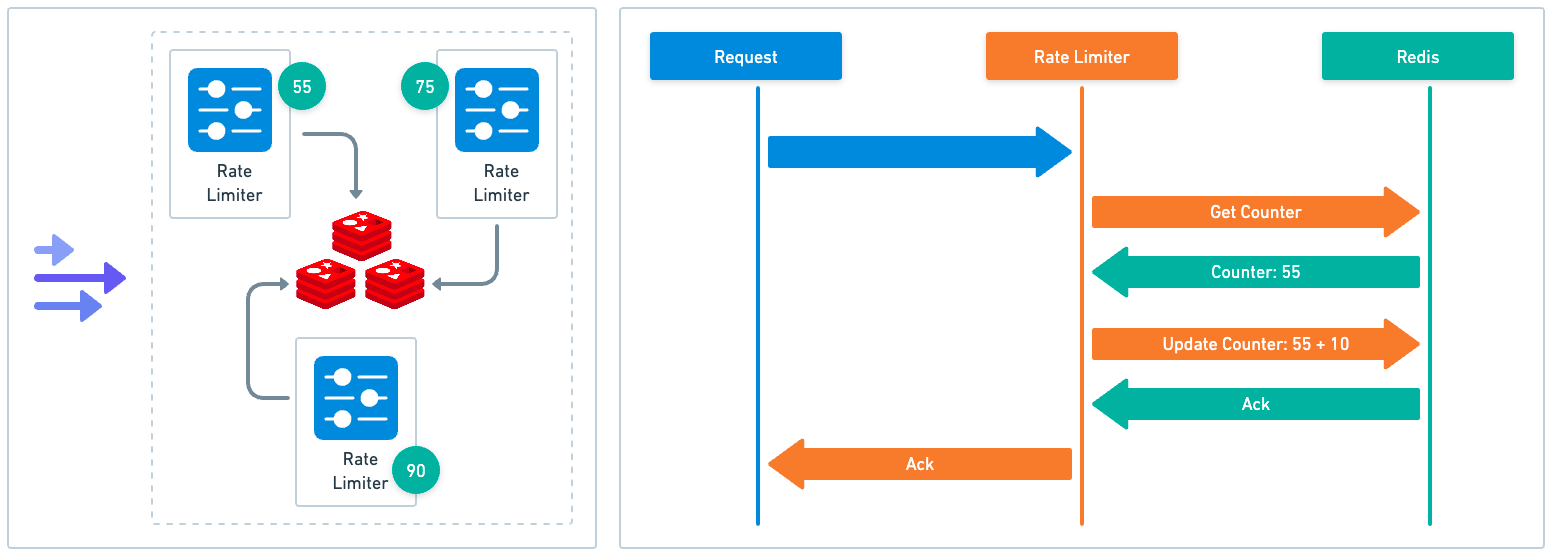

When rate limiters are distributed across a system, it presents a problem as each instance may not have a complete view of all incoming requests. This can lead to inaccurate rate limiting.

For example, let’s assume we have a cluster of reverse proxies, each running its own rate limiter instance. Any of these proxies could handle an incoming request. This leads to distributed and isolated rate limiting states. A user might potentially exceed their rate limit if their requests are handled by multiple proxies.

In some cases, the inaccuracies might be acceptable. Referring back to our initial discussion on requirements, if our objective is to provide a basic level of protection, a simple solution allowing each instance to maintain its own states might be adequate.

However, if maintaining accurate rate limiting is a core requirement - for example, if we want to ensure fair usage of resources across all users or we have to adhere to strict rate limit policies for compliance reasons - we will need to consider more sophisticated strategies.

Centralized State Storage

One such strategy is centralized state storage. Here, instead of each rate limiter instance managing its own states, all instances interact with a central storage system to read and update states. This method does, however, come with many tradeoffs.